Oceanus asks his son Niger what makes him flow all the way through east to west. Niger answers with a completely irrelevant speech (whose only point is to show off the author’s learning) about how it is not strange that he can mix his fresh water with Oceanus’ salty one, because the soul can both mix with and stay separate from the body. So Oceanus has to repeat his question once again and Niger this time answers it was because of his daughters. He considers them perfectly handsome with their black skin which does not age and black curly hair which does not go gray. Unfortunately, his daughters learnt that the European poets prefer to sing the praises of blue-eyed blondes. The Ethiops also used to be fair-skinned before Phaeton in a driving accident drove his father Sun’s chariot dangerously close to the earth. When the daughters of Niger learnt about it, they cried so much that the river became swollen with their tears. Niger tried to show them the error of their thinking, but once a woman sticks to an idea, there is no talking her out of it.Then one evening a miracle happened and surely it was a miracle because the Ethiops never dream (something that Jonson learned from Pliny). When they were sitting around a lake one evening, a mysterious face appeared in the lake. We’re going to learn what it said in the next post, but I would like just to observe that Jonson in a sense anticipated much of current thought about how white-dominated culture imposes its own ideal of beauty on other races (viz. Toni Morrison).

Month: April 2016

Ben Jonson – “The Masque of Blackness”

The masque was a complicated and vastly expensive multimedia extravaganza, combining music, dance and spoken word, aimed at obsequious flattery of the king. The currently fashionable approach reads them as “subtly interrogating” and “subverting” the ideology of the Stuart monarchy, but honestly, it takes some proper lit-crit credentials to see all that subversion. We’re talking about a theatrical genre where the whole stage was constructed in such a way so that the king would have the best view. The level of elaborateness can be judged by the fact that Ben Jonsons’s description of Inigo Jones’ setting takes one whole page – which is basically the ocean with nymphs, tritons, sea creatures, all of them moving and the allegorical figures of Oceanus and his son Niger in teh centre. The masque is going to take place in Africa, so expect some highly controversial (for us, that is) use of blackface.

Aemilia Lanyer – “The Description of Cookham” (the end)

After describing Margaret Clifford as an exemplary Christian, constantly meditating upon the Old Testament heroes and imitating them in her behaviour, Lanyer moves on to sing the praises of her daughter and only surviving child Anne, later on married to the Earl of Dorset. Lanyer mourns Anne’s marriage which separated them, but she can always love her from afar, the same as we lowly-born can love God. She can always rely on her memory of the sweet moments they spent together. Then she proceeds to describe Cookham’s grief after the ladies left, which is basically just the first part of the poem in reverse: the trees lose their leaves, birds sing only sad songs, the whole house is covered with dust and silence. One affecting episode is when Margaret Clifford kisses her favourite oak goodbye, and then Lanyer “steals” the kiss from the tree. She herself does not kiss the tree, because she is afraid she might lose the precious kiss. The poem ends with Lanyer expressing hope that this poem may preserve the memory of Margaret Clifford’s virtues for all posterity.

Aemilia Lanyer – “The Description of Cookham”

Ah, English stately country houses. They inspired countless poems, novels and TV series. But Lanyer’s poem has the honour to be the very first country house poem published. (Ben Jonson’s “Penshurst” may have been written at the same time or earlier, but it was published later.) So Lanyer is in a sense the mother of the genre which gave us Downton Abbey. But her poem is not about the love lives of the daughters of an earl. Instead, it is a rather bitter-sweet nostalgic look back at Cookham, where Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland, spent some time and it seems it was a very important period for Lanyer too. We do not know how she came to stay there and in what capacity, but she indicates she dates the reception of her “grace” – meaning both her religious conversion and her poetical talent – from “Her Grace”, i.e. Clifford. Now the lease is over and they are leaving. The poet is reminiscing about how they came first here in spring and how the whole house and the surrounding countryside seemed to dress itself up in its finery to celebrate the Countess. The only grating note to a modern reader is the observation that the little animals come to frolic, but when they see the bow in the Countess’ hands, they run away. The most beautiful place in the whole estate is a big oak on a hill, which Lanyer compares to cedars or palms, trying perhaps to evoke biblical echoes. The simile is not a successful one, since the oak is portrayed as spreading its great arms, desirous to hide the lady from the sun, while palms are notoriously bad for giving shade. Apparently you can see thirteen shires from the summit of this hill. This is the area where the Countess liked to wander, and the beauty of nature around her inspired her to meditate upon its Creator. She also read often the Bible there.

Aemilia Lanyer – “Eve’s Apology in Defense of Women”

Another poem from Salve Deus, this is not Eve delivering an apology for herself but rather the poet, delivering an apology for her and all womankind to Pontius Pilate, of all people. Pontius is about to pass the sentence on Jesus and the speaker tells him not do it, especially since he’s been warned by his wife. If Pilate condemns this most innocent man, the fault of Eve pales in comparison, especially since she did it only out of ignorance (falling dupe to the serpent) and her good heart (sharing the wonderful fruit with Adam). Adam, on the other hand, was much more to blame since he had been warned by God. (So was Eve and I feel Lanyer uses some special pleading here, arguing that Eve was innocent because she was tricked by the serpent but Adam should have known better.) Pilate’s sin is much greater than Eve’s sin, Lanyer argues, and therefore men should stop using Eve’s name as a stick to beat all women with and take a long hard look at themselves. So Adam and PIlate, men who should be theoretically wiser and stronger, are much worse than Eve and Pilate’s wife, standing for all the womankind. Lanyer ends with one more exhortation to Pilate not to sentence Jesus, which of course she knows is quite futile. She also skirts the interesting theological question: if Pilate had pardoned Jesus, the whole salvation plan would have come to nothing. A similar argument of “felix culpa”, the blessed fault, was actually advanced when speaking about the Fall – without the original sin, the Incarnation wouldn’t have happened.

Aemilia Lanyer – “Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum” (ctd.)

In the next prose text “To the Virtuous Reader” Lanyer makes a spirited defense against women-bashing, so popular in her times and not only her times. The interesting thing is that she criticizes first of all women who fall into the internalized patriarchy trap by talking trash about other virtuous women in particular or talking trash against women in general, as if they forgot they were one of them. (Seriously, if you are one of these women who humblebrags “I never have friends among women, women are boring and superficial”, leave this blog and don’t bother to read.) Ladies! No more women bashing! Men are perfectly capable of doing it themselves and it’s not awfully nice of them either. They forget they wouldn’t be here without women and so let us forget about their unjust accusations, treating them rather as spurs to make us even more virtuous. Then Lanyer quotes several biblical heroines who won over men’s pride and arrogance: Esther, Jael, Judith and Susanna. It’s not an altogether new trope, as a lot of women writers found solace in the biblical heroines, but it’s interesting that Lanyer focuses on those who managed to exact brutal revenge for the wrongs done to themselves or their nation (even Susanna’s judges were executed, if I remember correctly). Then she moves on to the New Testament, pointing out quite correctly that Jesus was throughout his life surrounded by women, in his last hour thought about his mother and after his resurrection showed himself first to a woman. Lanyer ends with an encouragement to all good Christians and honourable men to speak well of women, adding modestly that she hopes this small book may help.

Aemilia Lanyer – “Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum”

Aemilia Lanyer was born Aemilia Bassano; her father was an Italian musician, possibly Italian-Jewish or Protestant escaping the religious persecution. She was always hanging around the court circles, as her father, husband and eventually her sun were all musicians employed by various aristocrats. As a young girl she was the mistress of the much older Lord Hunsdon, who however, married her off to Alfonso Lanyer when she got pregnant. Her half-Italian or half-Jewish roots, suggesting she might have been a brunette, combined with the fact that Shakespeare’s troupe did perform in Hunsdon’s household in the 1590s (but it was when Hunsdon’s affair with Lanyer was already over) gave some rise to speculations that she might have been the Dark Lady from Shakespeare’s sonnets, but of course we don’t have any definite proofs.

Aemilia Lanyer is the author of only one volume of poetry, containing the Passion poem referenced in the title, another country-house poem (about which I am going to write in a few days) and a lot of dedicatory poems to various noble women, whose patronage apparently Lanyer tried to attract. It is interesting that Lanyer deliberately chooses only women. Many critics read it as a feminist gesture, especially when read in the context of the two main poems: the Passion shown through women’s eyes; Cookham residence as a utopian women’s paradise. But I also tend to think Lanyer wanted to appear extremely proper and after her well-known past with Hunsdon she didn’t want to make an impression that she was again on the prowl for another well-heeled lover as well as a patron.

A short text “To the Doubting Reader”, originally printed at the end of the book, explains the title (which is a loose paraphrase of the words pinned on Christ’s cross) explains that the words came to Lanyer in a dream, many years before she even thought about writing this volume. The next text is the dedicatory poem to Queen Anne, James I’s wife. It is for the most part a run-of-the mill dedicatory poem, with the poet flattering the recipient of the dedication and apologizing for the numerous defects of her poetry. The interesting points are where Lanyer promises to present the Queen with the defense of the biblical Eve, making the Queen a judge of whether her version of the events agrees with the biblical one, and if it is so, why are women blamed more than “more faulty men”? She also admits that as a woman she does not have much learning, but she presents her poetry as a work of Nature, not art or learning.

Izaak Walton -“The Life of Dr John Donne” (the end)

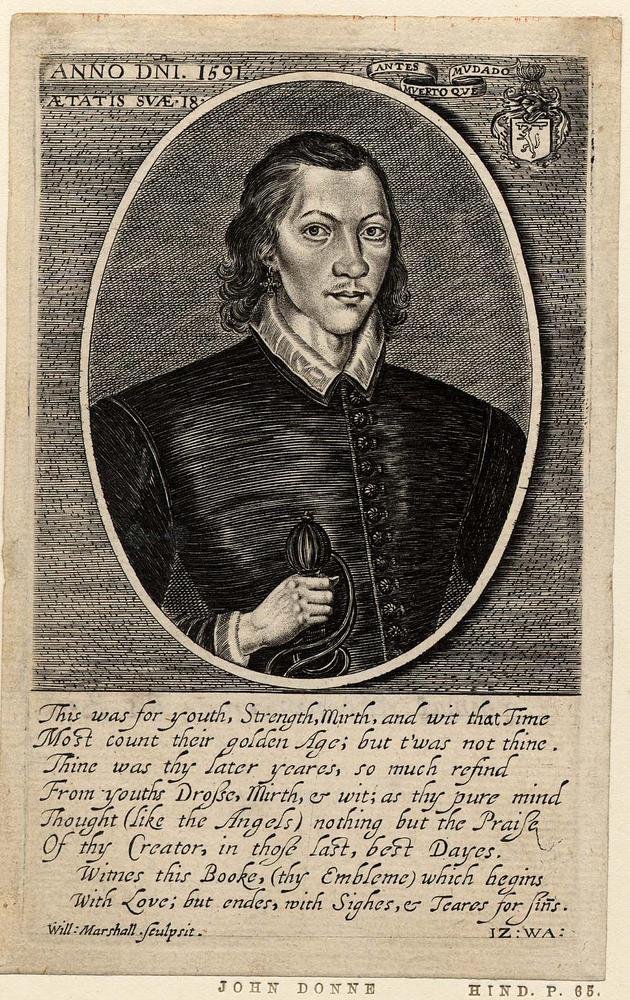

Walton ends his description of Donne’s funeral effigy by reminiscing about the portrait of young John Donne he has seen – Donne in this picture is 18, has a sword and is fashionably dressed. The portrait bears the Spanish motto “Antes muerto que mudado”, i.e. “Rather dead than changed”, which Walton somewhat erroneously translates as “Oh, how much shall I be changed before I am changed!” He suggests his readers should juxtapose these two portraits in their minds and meditate upon the extent of changes in Donne as well as the changes in themselves that are going to come. Donne himself very often pointed out to this fact and he considered his life before he took holy orders as non-existent. Then Walton moves to Donne’s final days. Donne takes farewell of his beloved study and goes to his bedroom, where for a week he is visited by his friends who want to say goodbye and receive his benediction. Then he takes another week to settle all his worldly affairs, after which his servants are ordered not to bother him anymore, because he wants to concentrate on eternity. After that Donne lies expecting his death, although he has been expecting it for a long time. In his previous serious illness he felt ready to die and he prayed God to keep him in this state, should he get better, until his eventual death. So he lies in bed for fifteen days, able to speak and pray almost until the very last minute. When he is no longer able to speak, Walton writes, it is because he is already capable, like angels, to communicate telepathically with God. Then he looks into heaven, sees the vision of God, closes his eyes and positions his body in such a way that those who are going to wrap him in his shroud do not have to change it at all. It is really impressive and reads like something from The Tibetan Book of Dying, except that I suspect Walton edited a lot of pain out. Some sources say Donne died of stomach cancer and it’s not a painless death.

Donne is buried, as he wished, at St Paul’s in the place he himself selected long time ago and used to pass every day. Although he wished for a private funeral, it is attended by numbers of people, his friends and fans. Anonymous people cover his grave with flowers every day until it is walled up back again. Another nameless admirer writes a short epitaph with a coal on the wall above it “Reader! I am to let thee know/Donne’s body only lies below/For, could the grave the soul comprise/Earth would be richer than the skies!” Yet another anonymous donor sends one hundred marks to his executors for the monument. The donor turned out to be Dr Fox, but it was not revealed until after his death. This is surely one of the very few examples in history when the doctor erects a tomb monument for his patient (and isn’t it in the end a kind of bad publicity?) The biography ends with a list of all Donne’s virtuous: learned, intelligent, pious,charitable etc. and with a pious hope that although Donne’s body is now just a heap of ashes, Walton shall see it reanimate.

The portrait of Donne as an eighteen-year old, via The British Museum. Goodbye, John Donne. I shall miss you.

Izaak Walton – “The Life of Dr John Donne”

Walton was Donne’s friend/fan – a generation younger, very much looking up to him. The excerpt in the NAEL is about Donne’s preparations for death. Walton says apologetically that nobody in this world, even the saintliest persons, are completely free from self-love and thus Donne let himself to be persuaded by Dr Fox to have a tomb monument carved for himself. A totally holy person would choose to be buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave, I presume. However, the design of the monument was Donne’s own. He asked a carver to carve a wooden urn for him and also to prepare a board of approximately his height. I’m not sure and Walton does not say it clearly whether the board was the one used by the painter later. Anyway, Donne posed for his last portrait standing on this urn and wrapped in a shroud, like a dead body, with his eyes closed and his face turned to wards the east, from which his Saviour was going to come. It’s very impressive but also… a touch melodramatic? But these were the conventions of the era, and who can say our way of dealing with death, that is putting it out of sight, is better? This picture he put then at his bed’s head and looked at it everyday until the end of his life. In his will he bequeathed the painting to Dr Henry King, his friend from St Paul’s, who ordered a sculpture of white marble designed on its basis. Donne himself composed a rather modest epitaph in Latin, which lists as the main facts of his life his birth, studies, the date he took Holy Orders and his death. The monument survived the Great Fire and can be still seen at St.Paul’s. I know it’s a total coincidence, but I like to think the fire in its fury spared the effigy of this most fiery poet.

[Image by Kieran Smith via Findagrave.com]

I had a brainwave today – John Donne is, in terms of versatility, Ralph Fiennes of English poetry. He can be funny, he can be scary, he can be sexy, he can be a suffering lover, he can be even a gay woman. OK, that’s the role Ralph Fiennes has not played yet, but who knows? And look at this portrait of young Donne, couldn’t Ralph Fiennes with his angular face play him? His brother Joseph perhaps has better natural colouring, but Ralph is a better actor.

John Donne “Death’s Duel” (excerpts)

This is Donne’s last sermon, preached just a few days before his own death in presence of King Charles and justly considered to be his own funeral sermon. Our whole life is, Donne argues, a passage from death to death: in our mother’s womb we are like dead, because we have eyes that see not and ears that hear not. We are even worse than dead, because in our grave we breed the worms which eat us and then kill them (Donne like his contemporaries believed that worms were born out of putrid matter) but if the child dies in its mother’s womb, it kills its own mother, becoming a parricide. In the womb we live in darkness, which prepares us for the world of darkness, and are fed with blood, which teaches us cruelty. I wonder if Donne thought about his own wife, who seems to have been killed by being throughout their whole marriage constantly pregnant or nursing. Also, the passage is so shocking to modern sensibilities. We are so accustomed to sentimentalizing maternity in popular culture and of course we know more about fetal development and the whole anti-abortion propaganda (even if you are pro-choice) permeates the public discourse to a large degree. So the whole argument of Donne, presenting the child as blind-and-deaf potential killer really takes one aback.

From this death we proceed into another death, wrapped in our placenta like winding sheath. Only Christ’s body did not see corruption and so won’t the bodies of those who are going to be alive (lucky them!) at the day of the Last Judgement. But we are going to undergo the third death when we are going to be eaten by worms. Donne then paints some grisly scenes (using a lot of references to the Book of Job), when worms, which he calls our “mother and sister” are going to be joined in an incestuous marriage with us. Death, a great leveller, is going to treat the same both happy and unhappy ones, kings and poor people. The sermon ends with an exhortation to the listeners to contemplate Christ’s Passion and await the resurrection.

Since this is the last text of Donne in this selection, I can say now – I love him! Dare I say, as a poet I like him more than Shakespeare? He is my favourite writer from the NAEL so far – he has incredible range, writing both about sex and spiritual love, God’s love and his own feelings of worthlessness, sin and redemption. Of course like all writers he has his hang-ups, or shall we say, favourite motifs he returns to over and over again – man as microcosm, alchemy – but the scope of his interests is still dazzling. The language is fresh and direct, the poems, especially those with uneven lines, seem to be the exclamations coming right from the heart. Even when his syntax gets obscure, he richly repays the trouble of untangling it.

I am not quite done with Donne (to repeat his own joke), because the next excerpted text is Walton’s biography of him, so that is coming soon.